Minari Review: A Beautiful Film About Family And Belonging That Transcends The American Dream

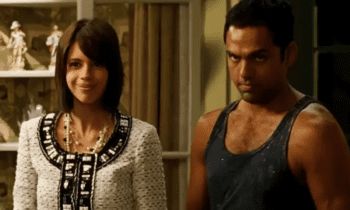

As you read this, Minari has already won a Golden Globe for Best Foreign Film, amongst other honours at the Sundance Film Festival, where it premiered a year ago, and the American National Board of Review. The film is a semi-autobiographical story inspired by the immigrant experience of its director Lee Isaac Chung, in which a South Korean family moves into 1980s rural America, specifically Arkansas, and has to both make a home and feel at home there. Starring Steven Yeun, Han Ye-Ri, Noel Kate Cho, Alan Kim, Youn Yuh-jung and Will Patton, Minari has been dubbed as a beautiful take on the immigrant experience in its search for the American Dream, with quite the universal appeal.

I’ve often been told, as advice to the aspiring writer, to write what I know. And to me, Minari is perhaps the biggest proof that there’s no better story than the one that draws on your own experiences. Because me, I love Minari for its littlest details, which make the story more about a family, their love for each other and how it manages to grow and survive through the challenges of finding home and a sense of belongingness in a new surrounding. The motions it goes through, the struggles, the emotions, these could easily be the story of any family that’s going through a change, staking all its hopes on that one big risk they’ve taken, and hoping that despite initial misgivings, it all works out in the end.

This family-first, identity-second approach is what makes Minari so much more personal and transcends the theme of immigrant identity.

View this post on Instagram

What’s Minari about?

The Korean American Yi family moves from California, where it had been since their move from Korea, to Arkansas, because the Jacob Yi has a dream—to farm in his backyard, grow Korean vegetables and sell it to vendors in Dallas. His wife, Monica, isn’t too happy to have their family thus uprooted and moved into a their new home that is nothing like her husband promised her would be, and has much sparse Korean community. What’s worse, Jacob plans to do everything himself rather than hire services for water and labour, seeking help only from a kooky but religious local, Paul. But her chief concern is maternal—their younger child, David, has a heart problem. And this land far away from civilisation that looks like paradise to her husband, feels deserted and too far removed to Monica.

Jacob and Monica also work at the local hatchery, sexing chicks, while their children, Anne and David, have to fend for themselves. And so they arrange for Monica’s mother Soon-ja to travel from Korea to look after them. As David cribs, Soon-ja isn’t his idea of a typical grandma, because his American upbringing tells him grandmas bake cookies. Soon-ja smells too much of Korea which, to him, is not home like America is. And yet, she’s probably much more American in her carefreeness than either of David’s parents are.

As the Yi family struggles to stay intact, put down roots and grow, faced with as many issues as Jacob’s 50-acre DIY farm or their assimilation in the local community does, unbeknownst to them, a lesson in resilience and adaptability is flourishing easily and nonchalantly by a stream in their backyard.

There’s a very subtle exploration of themes in Minari

I believe I could go on and on about the smallest of scenes and the deep ways I could interpret them for myself, and not necessarily as intended by director Lee Isaac Chung. But a particular one that comes to mind is when David asks his father where the smoke is coming from at the hatchery, and Jacob says, it’s from the place where they burn the male chicks because they don’t make good meat, and tells him that it’s a sign they both, men of the Yi house, should find ways to make themselves useful. Such a simple thing to tell a child in jest, and yet it carried so much burden of the masculine responsibility to be the provider of your family. Haven’t we see that a lot in our own homes?

Later in the film, we hear Jacob tell Monica that he wants his children to see him succeed at at least something. And this little conversation about the male chicks comes back to you, with another layer of meaning, and clearer understanding of what drives Jacob to be so relentless in the pursuit of his dream.

I love this understated brilliance of Minari. Nothing is repeatedly underlined or overtly emphasised to drive it home. In fact, I wonder if this subtlety was intentional, because it reminded me of a new entrant silently tiptoeing to assimilate itself into an already settled crowd, without causing much disturbance.

Minari puts family first, and identity second

Minari‘s storytelling seamlessly blends experiences that are uniquely Asian and those that could easily be universal, not tied to identity but more to family dynamics.

In an adorable, funny and telling scene, as both Jacob and Monica fight, Anne and David make paper planes inscribed with “Don’t Fight” and shoot them at their parents. Because as Asian kids, we know very well that not interfering in elders’ conversations is how you show them respect. The obsession with Mountain Dew, the hospitality shown to guests, Monica’s belief in home remedies and superstition despite being an otherwise practical person, Soon-ja overriding her daughter and letting David run as much as he wants, and taking back the $100 donation Monica put into the church collection because she knows her daughter might need it later…. I thought these are all scenes that even I as an Indian kid could identify with.

And then, there were scenes between Jacob and Monica, or Soon-ja and David, and even the entire family, such as the climax, that had a much more universal appeal. It was all about family, and it could have been any family that was making a drastic change in the way they lived or spent their money, or raised their kids. Jacob could’ve been just a man trying to provide for his family by making a risky investment. And Soon-ja could be just another grandma struggling with generation gap and finding out that the way to connect with her grandchildren was, perhaps, time and unconditional love.

As for the kids, they could’ve been both, immigrant children struggling to reconcile their dual identities or children who were just trying to find their place in a new town, having moved from California to the Ozarks. This ability to balance both was something that flowed so easily through the film, instantly endearing it to whoever was watching, irrespective of age, gender of nationality.

Of what I have seen, most stories that are trying to capture the immigrant experience are more about the person or people in relation to the society they are adjusting into. But Minari feels a lot more about a family’s adaptability, and constant effort to stay true to each other, with little interference from the outside world. And I love that, because wouldn’t you want to set up your own home properly before you let the neighbourhood in?

With Minari‘s nomination in the Foreign Film category at the Golden Globes 2021, which it won, the question then remains why a film with such universal appeal would still be put in that category, simply because of a language rule?

Minari, Nomadland and the subtle art of visual storytelling without letting it overpower

From perhaps the very first frame, Minari reminded me so much of another Asian filmmaker, Chloé Zhao, and her Golden Gloeb winning film, Nomadland. I mean, the themes very poetically overlaps—Minari is a film about home and finding a sense of belongingness through one’s family. Nomadland says that a house is not a home; but home is more of an emotion, a feeling that can be tied to anything: a vehicle, the open road, and even to a person. Both also speak to a second coming of sorts, where the Yi family decides to persevere and come back stronger, and Fern decides to live her second innings on her own terms.

I found a lot of parallels between the two films’ visual storytelling too, particularly in the way Minari cinematographer Lachlan Milne used open spaces, and what they could mean to different people in the films and those watching the films too. To me, someone who is absolutely into the whole city life hustle bustle, an open space like the one next to the Yi home might feel freeing for some time, but eventually could be isolated and dwarfing. It was something that Minari’s Monica felt; while her husband, Jacob, much like Nomadland‘s Fern and her fellow nomads, saw it as the freedom to build their version of the American Dream.

Similarly, just as the cramped van that was Fern’s home lightens up by the end of the film as she lets go of her baggage, the Yi home, which began looking like this drab and dull house, gradually becomes brighter and more like a home as the family grows comfortable in it.

Both Nomadland and Minari are masterclasses in subtlety, especially in the way they keep darkness at bay, but never so out of sight that you forget about its existence. When David meets a boy in church, his distinct Asian features are instantly questioned but mocked in almost a naïve, childish manner as the American boy instantly turns it into a play for friendship. Nothing irreversibly bad ever happens to anyone, and everyone gets a chance to rectify their mistakes because it’s all trial and error, adapting to these new occurrences. But at every step, you’re constantly aware of how this could all easily go bad for them, in their isolated surroundings, where they were alone and didn’t have much help or an external support system.

Another reason this might have been, I feel, was because of the film’s semi-autobiographical quality. Minari draws on Lee Isaac Chung’s childhood experiences, which makes young David not just a part of this story but also, in some ways, a future narrator. As a child, he is this non-intrusive observer, who doesn’t really grasp the seriousness of what might be happening, but he does seem to know the essence of things.

A special mention must also go out to the music by Emile Mosseri, which adds an additional layer of wonder and delight to the outdoor scenes, like the ones with little David running or strolling about. Again, no overpowering, the music felt more like it was forming these gentle ripples of light on water, a perfect accompaniment to the film’s commitment to being subtle.

Minari flourishes because it is fertilised by some powerful performances

I couldn’t pick one if I had to, really. I thought the actors’ performances reflected so much of their characters’ place in this story. The Walking Dead‘s Steven Yeun and Han Ye-Ri do most of the heavy lifting, and are brilliant as Jacob and Monica. Noel Kate Cho as the elder sister is so relatable, I can attest to that, being one. Youn Yuh-jung as the fun Korean grandma is pretty much the crackling scene-stealer who comes suddenly, makes you wary of her, but then has your heart. Will Patton’s Paul is unquestionably heartwarming. But Alan Kim is hands down a favourite! His scenes with Yeun and Yuh-jung are some of my favourites!

View this post on Instagram

Verdict

Minari is actually a plant, scientifically called ‘Oenanthe javanica’, or commonly known as Java waterdropwort, Chinese celery, Indian pennywort, Japanese parsley, water celery, or water dropwort. It originates from East Asia but it can actually grow anywhere without requiring much effort. Just find it some good, fertile soil, say, by the stream like Soon-ja did, and it’ll flourish. Much like the countless immigrants who’ve migrated for greener futures, found some good land, and settled there to make their own home, their own version of the American dream.

However, minari has this particular characteristic, where if it dies, it actually comes back stronger in its second season. And this little attribute has been poetically employed, as revealed by director Lee Isaac Chung, to give the film its title and a hopeful concluding message.

I say, message received absolutely! Minari is a beautiful film that is first and foremost about family and a sense of belongingness, and a story about the immigrant experience in chasing the American Dream second. Lee Isaac Chung embeds his film with these little details that can only come from understanding these family dynamics on a deeply personal level, and the actors carry it forth the rest of the way to deliver a subtly poignant film. It made me want to hug my folks with love, something we often forget to do while we go around chasing whatever it is we are chasing in our daily hustle.

Stop, pause, and hold each other up when things are failing. You’ll find a way to grow back stronger, as long as your roots are nourished and holding you on.

Minari is an A24 film, currently available on VOD.